Before advanced-flight simulators, there was Navitrainer

First Published: 18/09/23

‘Hooray! shouted Yertle. ‘I’m king of the trees! I’m king of the birds! And I’m king of the bees! I’m king of the butterflies! King of the air! Ah, me! What a throne! What a wonderful chair! I’m Yertle the Turtle! Oh, marvelous me! For I am the ruler of all that I see!’

- Dr. Seuss, Yertle the Turtle

So, a few months back, I posted a blog about an old poster I found at my local bookstore, Reader's Corner. It was about an Addressograph, and in the blog, we discussed what an Addressograph was, its origins, and we tried to estimate how old my poster might be.

It's been a while, and guess what? I've been visiting Reader's Corner often, and I have discovered many more amazing gems! I'm considering turning this into a blog series.

Usually, I love sprinkling my technical blogs with stories as there is something remarkably beautiful about understanding how things were introduced, rather than jumping straight into what they are about. In this busy day and age, it feels comforting to trace our steps back and reflect on the humble beginnings of a field. Although this is not an overly technical blog post, I believe that the spirit of my writing remains the same.

The Poster

Today, we will be exploring the following poster:

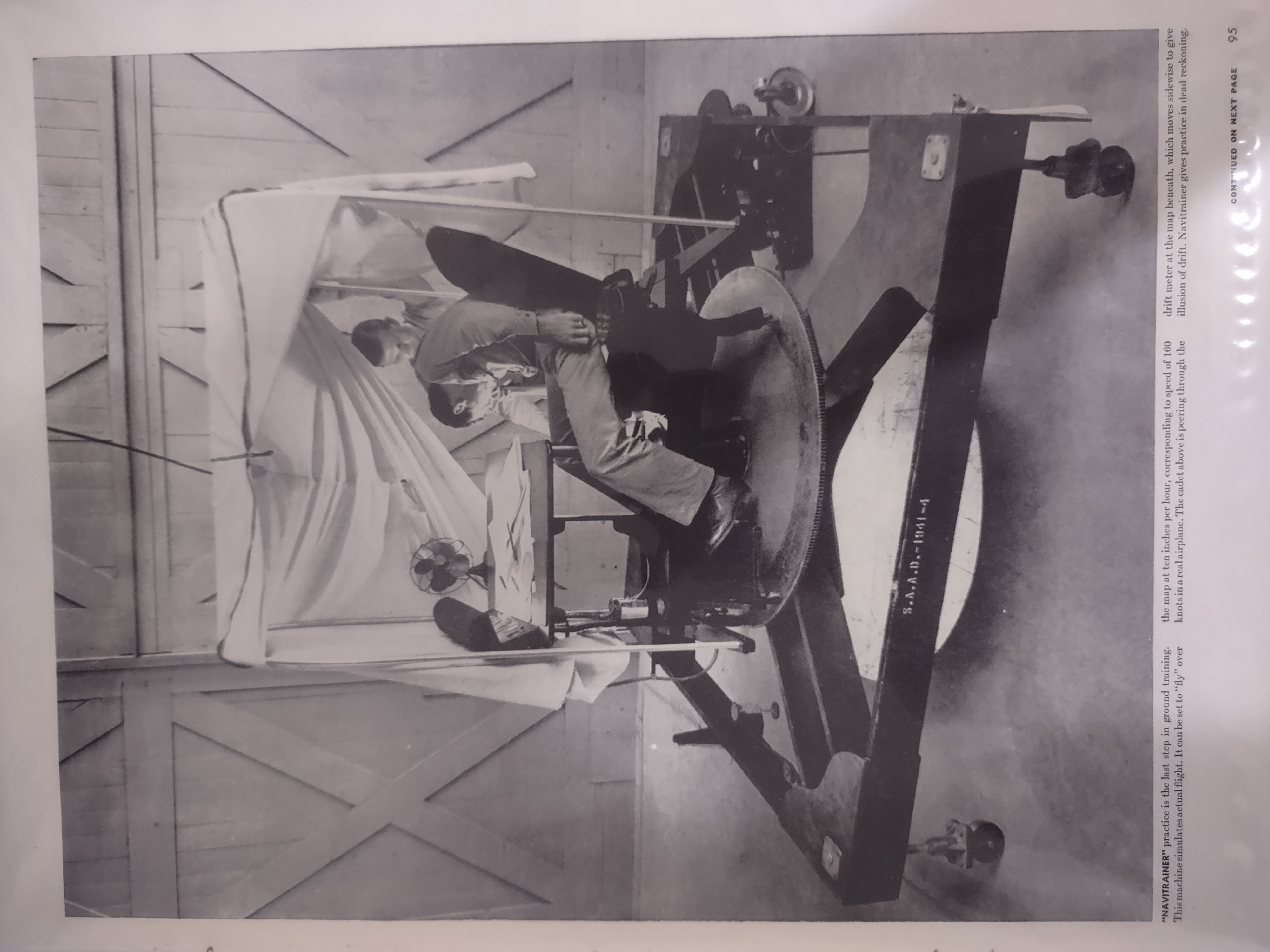

This poster shows two men using what is known as a navitrainer. The description of the poster says the following:

“Navitrainer” practice is the last step in ground training. This machine simulates actual flight. It can be set to “fly” over the map at ten inches per hour, corresponding to speed of 160 knots in a real airplane. The cadet above is peering through the drift meter at the map beneath, which moves sidewise to give illusion of drift. Navitrainer gives practice in dead reckoning.

Before we proceed, let's briefly explain the term dead reckoning mentioned in the description. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, it is defined as:

a way of calculating the position of a ship or aircraft using only information about the direction and distance it has traveled from a known point

In simpler terms, if a pilot knows their aircraft's airspeed and heading, and the time that has passed since the last known position, they can use dead reckoning to estimate their current position.

Interestingly, it is said that Christopher Columbus and many other early explorers heavily relied on dead reckoning and celestial navigation during their voyages. However, as you can imagine, this could lead to significant errors, especially on long voyages over the open ocean. Columbus famously underestimated the distance to Asia, leading to his accidental discovery of the Americas. If this tangential topic fascinates you, I encourage you to explore Dead reckoning and the ocean voyages of the past by C. V. Sölver & G. J. Marcus.

It's Origin

During one of my visits to Reader's Corner, I asked them how they curated these fascinating pictures. They enthusiastically told me how they would scour through old catalogs of Life magazines in search of these unique posters. Doing a reverse search on the description, sure enough, leads to one of Life Magazine's issues from September 28th, 1942. Apparently, Life magazine was running a piece onaerial navigation aerial navigation.

The article itself is fascinating, and I encourage you to explore it. It describes the science of navigation used by the U.S. Air Force's navigation officers. It starts by exploring pilotage (point-to-point flying by recognizing landmarks), followed by dead reckoning, and lastly, navigation using the stars. When discussing their instruments, the following was stated:

…. the Air Forces teaches their use in four stages. In stage one (below), plywood models define the principles of each instrument. In stage two (above), cadets practice exhaustively on demonstration setups of the actual instruments. Third stage (opposite page), puts cadets through the routine of a flight with all instruments mounted in a “Navitrainer” which crawls slowly over a map. The fourth stage of instrument training is carried out in the air. Here, with compass, drift meter, computer, sextant and radio, cadets guide their trainers through fog and Texas thunderstorms. After 15,000 miles of practice flights all over the U.S, they acquire a fierce absorption in their dials and computers that make them able to plot an accurate homeward course in pitch-black darkness while their bomber is bouncing through the flask of an enemy target.

So it seems like the functionality of Navitrainer closely resembles that of flight navigation simulators we see today. From the instruments they described, a sextant is used to measure the angle between two visible objects. Moreover, a drift meter is a tool used in aircraft to measure the drift angle, which is the difference between the direction an aircraft is pointing (its heading) and the direction it is actually moving (its course). It's kind of like trying to walk in a straight line towards a building, but there's a strong wind blowing from your right side, pushing you to the left. The difference in direction is known as the drift angle.

As you can imagine, strong winds can cause the aircraft to drift off its intended course. By using this device, pilots can measure this drift and adjust the aircraft's heading to compensate for the wind effect, thereby improving the accuracy of dead reckoning calculations.

Deconstructing a Navitrainer

Let's begin by asking ourselves what the US Army Air Forces aimed to achieve using this device. Well, in one of the confidential documents released by them, they mention the following:

Designed by Lieut. Col. C.J. Crane, new Navitrainer, time-cutter in training military flyers, simulates flight navigation on the ground and gives students nearly all the elements of actual flight, including day and night navigation over water or land, and even over overcasts where only radio bearings and celestial navigation can be used. Operational features of Navitrainer are detailed.

- Flying and Popular Aviation Feb '42 pp 70, 104, 106 2 illus

This reinforces our belief that the device was intended to be used as a flight navigation simulator for students. In a 1943 article on training devices in The Official Service Journal of the US Army Air Forces, the workings of a Navitrainer were explained in some detail:

The Type G-1 Navigation Dead Reckoning Trainer, more commonly known as the "Navitrainer", is a compact device supported on a triangular moving base. Problems in dead reckoning navigation may be simulated and the results recorded.

The Navitrainer is composed of three main assemblies: the navigator's car triangular frame and the windtroducer. The navigator's car contains the plotting table, drift meter, compass and other flight instruments. The car is totally enclosed by a canopy and is mounted on the frame, which moves in any direction and travels at a speed proportionate to the air speed of the simulated airplane. The windtroducer serves two functions. It introduces wind direction and velocity, and it supports a chart or map that is used as a reference for determining the simulated airplane's position or course of travel.

An instructor, who exercises supervision through an externally located instrument control box, can introduce drift and control the readings on the other instruments. This equipment operates from a standard AC light outlet.

However, there are still a few questions remaining. For instance, where is the windtroducer located in our poster? And how does it support the map that we see in the same poster? Furthermore, how is the speed being simulated?

These questions were fascinatingly explored by Ben H. Pearse in the February 1942 edition of Flying Magazine, where he wrote an article on Navitrainers. Ben's explanation is the clearest of all and paints a vivid picture of how the Air Force cadets were interacting with this simulator. From his article:

The machine consists of a wooden frame about seven feet square, mounted on wheels two feet off the ground, and supporting a navigator's “cockpit” so constructed that it revolves through 360° around a drift meter tube extending up through the center. The wheels supporting the wooden frame are operated by an electric motor which can be speeded or slowed to simulate speeds of from 150 to 400 m.p.h in any direction of the compass. The motor is geared according to the scale of the map laid on the floor or on the Windtroducer beneath the frame, so that if the plane's average speed is 300 m.p.h., and the map scale is 10 miles to the inch,the Navitrainer will move 30 inches in an hour. With enough patience, a sofa pillow and a few chicken sandwiches in his pocket, the student can cross the Atlantic, circle the British Isles and return the same afternoon. If he is really ambitious, he might keep right on going and circumnavigate the world, without even running off the hangar floor. .....

Below the frame is the Windtroducer, which at the will of the instructor produces all the vagaries of the wind with which the student navigator could possibly have to contend.

Fascinating indeed!

Conclusion

And that's it, folks! I encourage you to explore the Life magazine article and Ben's article in the Flying Magazine. Tangentially, I have been working on a ground-based Air Traffic Simulator in Rust. Please feel free to check it out and drop me your suggestions.

←