Before Xerox, there was Addressograph

First Published: 25/06/23

There is something in a treasure that fastens upon a man's mind. He will pray and blaspheme, and will curse the day he ever heard of it, and will let his last hour come upon him unawares, still believing that he missed it only by a foot. He will see it every time he closes his eyes. He will never forget it till he is dead—and even then Doctor, did you ever hear of the miserable gringos on Azuera, that cannot die.

- Joseph Conrad, Nostromo

Stumbling upon a gem

I've been a student at NC State for just under two years now, and one of the most fascinating aspects of it is Hillsborough Street. Surrounding the main campus, this lively and cheerful street is home to some great food and boasts the evergreen Bell tower at one end. However, its lesser-known gem is a bookstore called the Reader's Corner.

What's truly fascinating about this spot is that you can buy some incredible books at an incredibly low price. Outside the store, there are shelves filled with used books, and the remarkable thing about these shelves is that any book on the left side of the store costs 25 cents, and on the right, it costs 10 cents. And if that's not enough, they update these shelves periodically with a variety of books. The store's owner, Irv Coats, has been running it since 1980 and donates all the proceeds from the outdoor book sales to NPR.

The store itself is absolutely fascinating as well. You can scan hundreds of comics, most of which are priced at a dollar. They also have an extensive collection of science fiction and detective stories, as well as fun items like posters, which usually cost around $2.

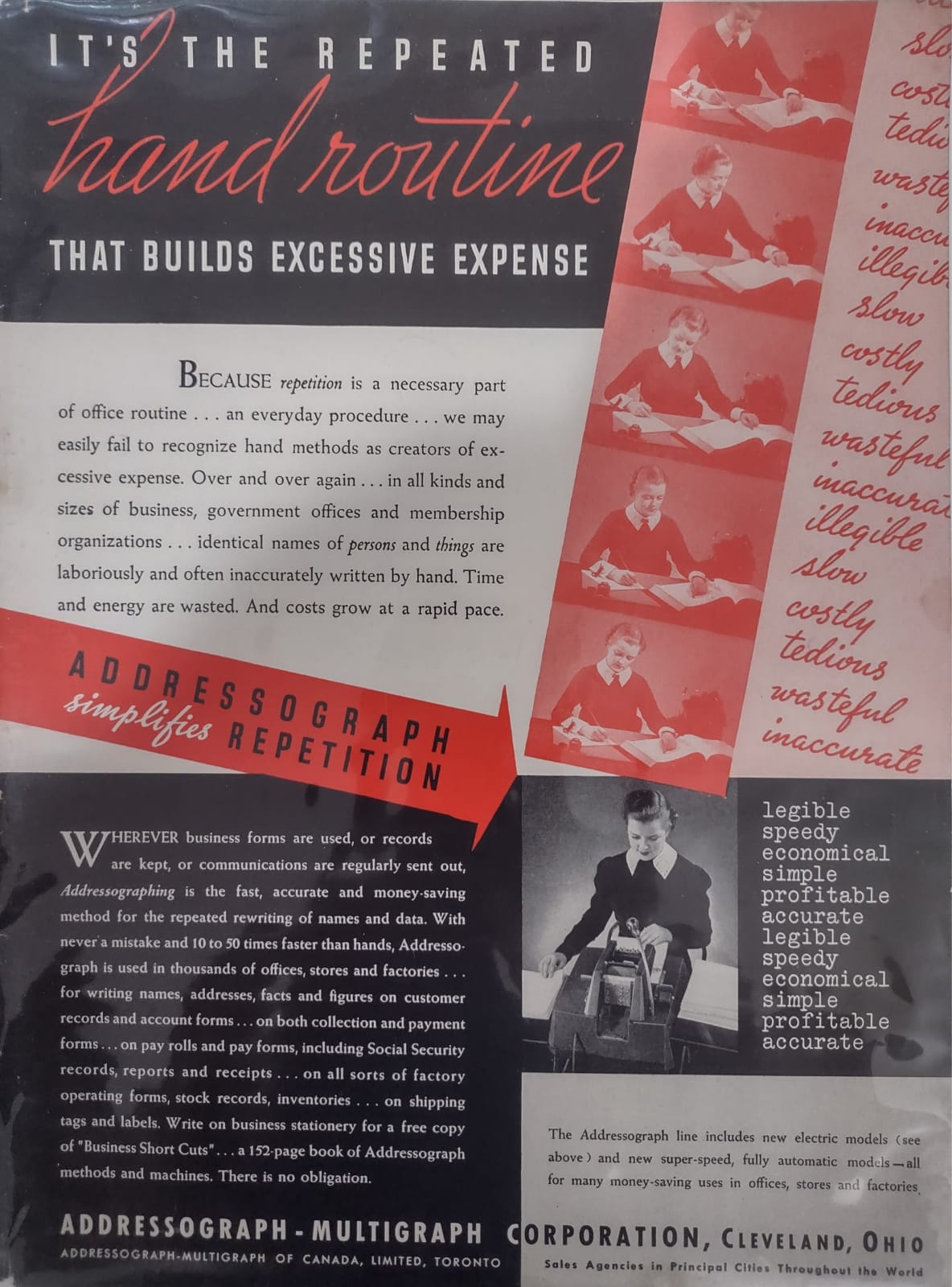

This month, when I visited the store, their poster collection caught my eye, and I decided to browse through their collection in the hope of finding inspiration for my next blog post. That's when I came across the following poster:

Truth be told, this was the first time I heard of an Addressograph. So what does it do? What was the motivation behind its creation? And how does it work? Let's take a dive into an Addressograph.

What was the motivation behind its creation?

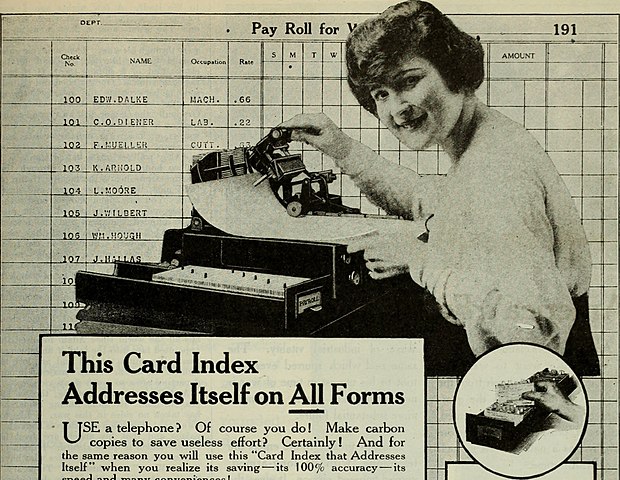

In 1892, Joseph Smith Duncan created the Addressograph, which is an addressing machine at its core. That is,

a business machine that automatically imprints names, addresses, or other information on successive envelopes or forms.

At a first glance, automatically imprinting addresses may seem like a small feat, even for the 1890s. In fact, in the early 2010s I recall sending handwritten letters to my grandfather and he'd reply to me with letters bearing his stamped address. He'd invested in a rubber stamp with an ink pad for this purpose. Eventually, he switched to using address stickers.

Given that a rubber stamp would have sufficed during the 1890s, why create a mechanical device like this?

Well, during a 1918 interview for the Manufacturing and Wholesale Industries of Chicago (Volume 2), J.S. Duncan shared his thoughts on experimenting with rubber stamps:

With as little prospect of getting another position as there was in those days (Duncan here is referring to the Panic of 1893), I began to wonder how I might use my small amount of capital in making a living. The addressing machine idea had been clinging to me persistently, and as I had a good deal of mechanical experience in my work at the mill, I decided to experiment with the hope of producing a device which could be marketed.

My first experiment was pretty crude. I glued the rubber parts of a number of hand stamps onto a big wooden drum. This drum was then revolved from one address to another to do the printing. The work was readable, and there was no chance to make mistakes in the addresses. But the drum only held a few names. How was it to take care of even a small mailing list such as we had at the bank? Clearly the plan was a failure, because it was not practical.

The motivation was to develop a more scalable version of the rubber stamp approach. It's worth mentioning that addressing machines existed even before the 1890s, but Addressograph emerged as one of the major victors of the 19th century. The Early Office Museum provides a more in-depth history of addressing machines. I also found Wright and Peck and H. Moeser's addressing machine from the 1860s particularly interesting.

Fascinatingly, Moeser's patent is concise and spells out how it operates:

The machine consists of levers, a slide, and a set of types, combined in such a manner that it is possible to print with it any number of names on papers or letters. Thus to print the names of subscribers on newspapers the following plan is pursued. The names (of persons or places) to be printed are set up in type in a column and secured in a form which moves by means of a slide beneath a stamp in such a manner that every Word in the column, one after another, is exposed to the action of the stamp, and so that paper after paper brought between the stamp and the types gets the proper impression.

Before the operation of the machine is to commence the whole set of names in the form is inked at once and put on the slide so that the first name in the column is right under the slit of the plate, and the impression is effected then by holding the paper on which the name is to be printed under the stamp and by pressing the main lever down. By raising the lever again the slide moves by the action of the spring-pawl so much that the second name of the column gets beneath the stamp, and if then another paper is brought under the stamp the second name will be printed on it by pressing the main lever down, and so forth, till the whole number of names is printed on the respective papers.

So, let's jump back to Addressograph. Did J.S. Duncan not have knowledge of Moeser's work? It seems that he didn't. In that same interview in 1918, Duncan stated the following:

Back in 1892 I was in charge of the books of a large milling concern in Sioux City, Iowa. Among other duties I had to see that a number of flour price lists and bids for grain were sent out each day to a list of people with whom he regularly did business. This addressing was a tedious job. It used to keep one of the young men in the office busy most of the time. Every now and then one of these bids would go astray through a mistake in the address, with the result that other milling companies would get the business. In a year's time these losses amounted to a good deal of money.

As I was a stockholder and director in the company, although the amount of stock I held in those days was necessarily small, I was much annoyed by this loss of business. I felt that there ought to be some way of addressing our cards mechanically, a way that would prevent mistakes and that would save most of the time and effort then wasted by the clerks in writing, over and over again, the same names and addresses.

So I looked for an addressing machine. I searched all the trade papers, and wrote to several office supply houses in Chicago, but to no avail. There was no such thing as a commercial addressing machine on the market; so I let the matter drop for the time being.

At this point, a natural question to ask would be, how does it work? And how is it different from Moeser's machine, as well as other addressing machines that came before it?

The How

The original Addressograph, created by J.S. Duncan had a simple yet remarkably ingenious start. In the 1918 interview, Duncan described how it worked:

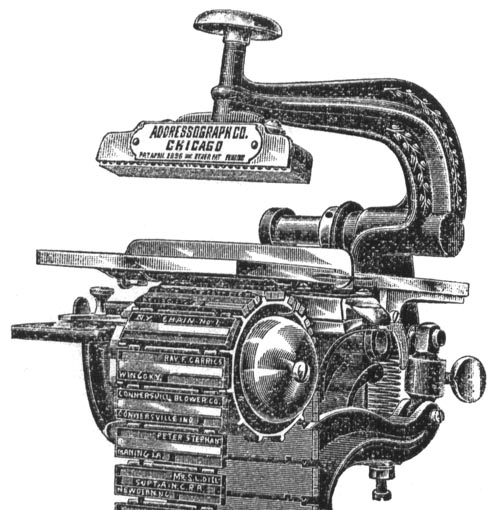

One day it occurred to me that the difficulty might be done away with by setting up the addresses in individual rubber type, and linking them in detachable chains of carriable length. I made a model along these lines and showed it to several of my business friends. Most of them thought the idea very clever, but all were skeptical as to its practicability; in fact, several of them laughed at the thing, and told me I was foolish to waste time in trying to commercialize a device of that kind.

But no doubting or ridicule could disturb my conviction. Encouraged by a very good friend, I came to Chicago in the latter part of '93 and rented a small room on Dearborn street where I proposed to begin the manufacture of the Addressograph.

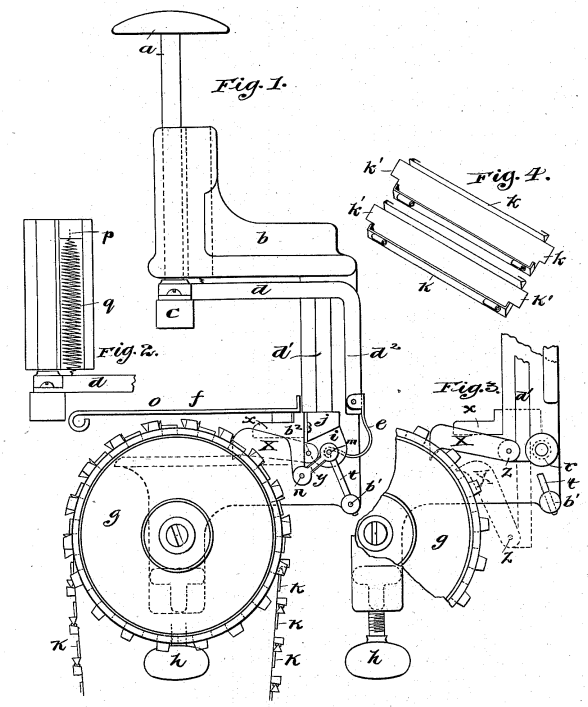

This is explained in much greater detail in his 1896 patent for Addressograph .

My invention relates to improvements in addressing-machines in which a chain of detachable type-plates is suspended over a rotating drum and a plunger or stamper capable of being driven downward upon the top of the drum carries a platen into contact at each movement of the machine with one of the type-plates, which are inked from a suitable inking device; and the objects of my improvement are to provide,

- first, a type-belt easily removable and capable of being compactly stored away when not in use;

- second, an inking device having a direct bearing on the type, without rolling or sliding, and in which the ink-pad is normally closed from air and dust;

- third, a simple and accurate means of rotating the type-belt so as to bring the name-plates successively under the platen;

- fourth, to dispense with all pulleys for the type-belt, suspending it from a single drum;

- fifth, to provide a detachable link which will retain the printing-surface and yet allow it to be easily removed, and in which any link can be easily removed from the chain, and,

- sixth, to produce a small compact addressing-machine capable of being easily clamped to the edge of a desk or table.

As Duncan found success after selling his initial machines, he worked on various iterations to improve his design. In the same interview, he said:

Enthusiastic over our success in selling these first machines, I had a hundred more built. These were arranged so that a foot lever could be attached, thereby leaving both the operator's hands free for feeding the envelopes. It was a much needed improvement, and served greatly to speed up the work of the machine.

This led to the eventual creation of the Addressograph Company in 1893.

Finally, what is this poster about?

At the bottom of the poster, Addressograph-Multigraph Corporation, Cleveland, Ohio is boldly mentioned. So, it's worth tracing back steps from this part. Firstly, how did this corporation come into being? Well, when J.S. Duncan decided to bring the Addressograph into production in the 1890s, he partnered with John B. Hall, a salesman who investigated the prospective market and helped demonstrate the product to business magnates. According to the Addressograph article on Made in Chicago museum:

By the early 1920s, John Hall had passed away, and Duncan was in semi-retirement, spending a lot of his time in Los Angeles with his wife Adelaide. Finally, in 1924, he elected to step away for good, with half the interest in Addressograph staying with the Hall family, and the other half acquired by another Chicago businessman, Frank H. Woods of Lincoln Telephone & Telegraph.

Woods installed Joseph Egerton Rodgers as the new company president, and by 1930, after some legal battles with the Hall family, the new ownership struck a deal to merge the Addressograph International Corp. with one of its chief rivals, the American Multigraph Co. of Cleveland, Ohio. The new organization, known as the Addressograph-Multigraph Corporation, ultimately centralized its operations in Cleveland.

Apparently, the merger was completed in 1932, and around 1933, the 152-page book titled “Business Short Cuts,” containing Addressograph methods and machines (as mentioned in the bottom-left part of the poster), was published. Hence, my guess would be that this poster is from the early 1930s. The quality of the poster is remarkably impressive for something that is nearly 90 years old!

So, what ultimately happened to this new corporation? According to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, the company experienced steady growth after World War II and by 1967, it had accumulated $400 million in sales from its parent and 27 subsidiaries. However, the emergence of Xerox in the 1970s had a major impact on their success. Despite making numerous changes and significant cuts to improve efficiency, the company ultimately closed its doors in 1982 and filed for bankruptcy under Chapter 11.

Conclusion

And that's it folks! I hope you enjoyed this dive down a rather obscure part of history. I'll continue making occasional trips to the Reader's Corner in search of hidden treasures like these.

←