Tinker Postman Collector Scribe

First Published: 13/12/24

Mister Postman look and see

(Oh, yeah) Is there a letter in your bag for me?

(Please, please, Mister Postman) I been waiting a long, long time

(Oh, yeah) Since I heard from that girl of mine

- Please Mister Postman, covered by The Beatles. Originally by The Marvelettes.

There is something about a dense medium that excites me greatly. For me, this goes beyond just technical articles and books, extending to urban city planning and even movies with rich, complex, and rapid-fire conversations. Take one of my favorite films, for instance — 12 Angry Men — a movie entirely set in one location, a jury room, where twelve men do nothing but deliberate the fate of a boy accused of murder. When it comes to city planning, I enjoy cities that are densely packed with hotspots, where I can travel almost anywhere on foot with the addition of some public transportation.

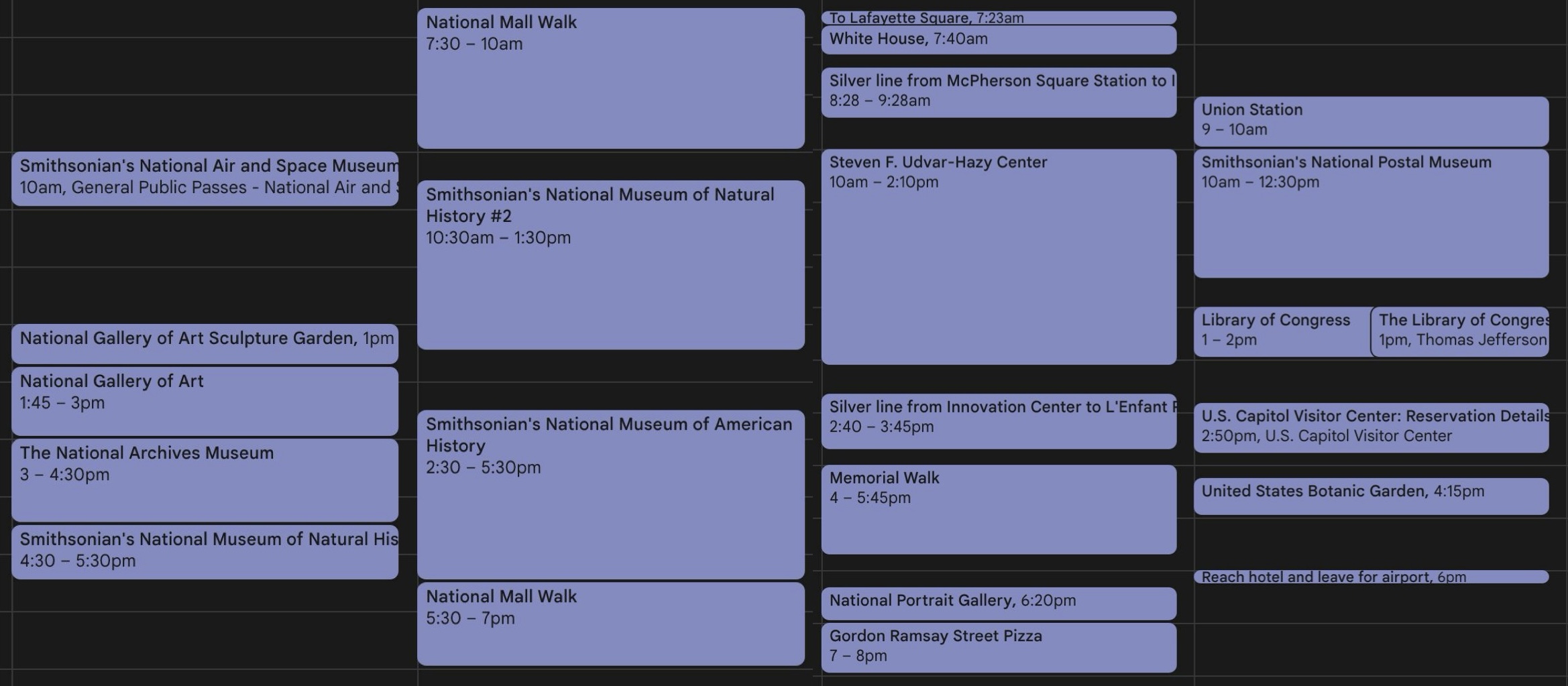

With a taste like that, visiting Washington, D.C. had been on my list for quite some time. This November, I finally managed to make it happen during my Thanksgiving break. For me, this trip was practically a frog’s leap away from where I live. Now, I am no travel blogger, and this is no travel blog, but the itinerary I designed for the trip exceeded my initial expectations to the point that I am happy to share it below:

Growing up, I admired Robin Williams’ monologue in Good Will Hunting:

….. if I asked you about art, you'd probably give me the skinny on every art book ever written. Michelangelo, you know a lot about him. Life's work, political aspirations, him and the pope, sexual orientations, the whole works, right? But I'll bet you can't tell me what it smells like in the Sistine Chapel. You've never actually stood there and looked up at that beautiful ceiling; seen that. …..

However, it is only now that I have fully experienced and internalized his words. I tell you, standing in the National Gallery of Art, among the works of Da Vinci, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Monet, Van Gogh, Picasso, and Pollock was quite an experience. Only now can I say that I have seen the thickness of Van Gogh’s strokes and the madness that likely lay within, as well as the dance of light and shadow that Rembrandt displayed. Vermeer’s work excited me the most, though — the use of light, the use of light! And the attention to detail. It was the most magnificent thing.

At NC State, I had the pleasure of taking Prof. Ben Watson’s class on Computer Graphics. Among his many readings, one involved “Allegory, Realism, and Vermeer’s Use of the Camera Obscura”. In my link logs, I very briefly summarized this paper as:

I came across this paper in my Computer Graphics class. Philip Steadman describes how Johannes Vermeer used a camera obscura to bring about his magnificent attention to detail. If this was indeed the case, it makes one wonder just how difficult it must have been for Vermeer to trace and paint directly onto the canvases without making mistakes. My favorite part in the paper is when Steadman describes the glass orb in “The Allegory of Faith” which allegedly provides a small glimpse of the camera obscura.

It’s a nice little rabbit hole to dive into. Hoppity hop, white rabbit flip-flop! There is also a fascinating documentary on this subject by Penn and Teller called Tim’s Vermeer. However, standing there in the gallery, I all but forgot about the camera obscura. It does that to you. Anyways, enough of being a romantic.

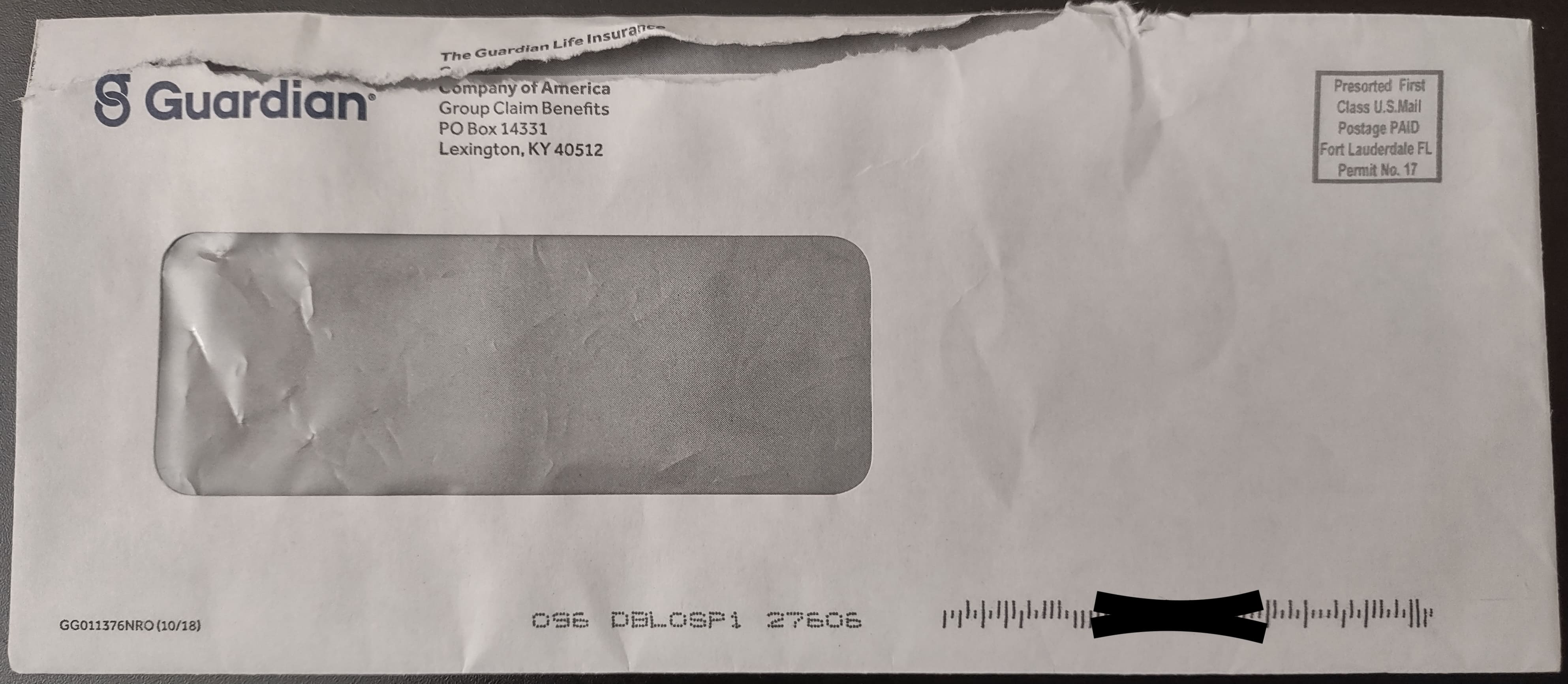

Let us shift gears to another museum — and the focal point of this blog — Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum. It is located on Massachusetts Avenue, right next to Union Station. Never would I have imagined that a postal museum could bring me so much excitement. The museum itself is quite small compared to the other Smithsonians. However, this, I believe, is its best feature — it doesn’t overwhelm you with information.

There are various permanent exhibits. One exhibit focuses on the “Gems of American Philately”, which includes stamps like the Penny Black (the world’s first adhesive postage stamp), a stamp from the 1765 Stamp Act, the 24c inverted Jenny stamp, the 29c Elvis Presley stamp, and, of course, the 5c Franklin and 10c Washington stamps (the first U.S. postage stamps). At one of the exits of that exhibit, there is a large table piled with stamps. The catch, though, is that you can take home only six complimentary stamps! It’s a perfect way to slow down the hands of time as you sift through the heap, sorting and filtering the stamps to your liking. They even provide free postcards for you to write to your family and friends!

What fascinated me the most, though, was their “Systems at Work” exhibit, which featured the automatic Carrier Sequence Bar Code Sorter, also known as CSBCS. From their exhibit:

For decades, mail carriers had to sort their mail into its delivery sequence before they went out on their routes. This process often took several hours. The Carrier Sequence Bar Code Sorter (CSBCS) was one of the first widely implemented machines that automated the sorting of mail down to the delivery sequence. Mail could go directly from the CSBCS to the carrier — in order and ready to be delivered.

Clive “Max” Maxfield’s blog post on the United States Postal Service (USPS) probably provides the best introduction to CSBCS’ role through the lens of USPS’ entire pipeline:

When you post a letter, it’s quickly transported to the nearest major mail hub. As soon as it arrives at the hub, the mail is fed into a machine that captures an image of its handwritten or printed address. This image is transmitted to powerful computers that perform incredibly sophisticated Optical Character Recognition (OCR) in real time. Based on this, additional software determines the destination that the originator of this piece of mail had in mind. It then accesses a national database to “fill in the gaps.” The result is translated into a POSTNET barcode that is printed onto the mail as it passes at high speed through the machine. This barcode is subsequently used to guide the mail throughout the remainder of its journey.

Next, the mail is sorted with respect to whichever major hub is closest to its ultimate destination. It is then transported to that hub. In the not-so-distant past, the mail would eventually end up at some main local mail facility. Here, the mail would be fed into a Carrier Sequence Bar Code Sorter (CSBCS), which would read its barcode and sort the mail into the Carrier Route Sequence ….. That is, the mail would be sorted based on the order in which it would be delivered by the carriers serving that community.

The old CSBCS machines were around 6 ft. wide, 4 ft. tall, and 12 ft. long. Approximately 4000 of these units were deployed at local facilities around the country. These machines performed their duties admirably for many years. But time moved on and they were eventually superseded by new technological developments. Now, the task of sorting the mail into the Carrier Route Sequence is performed at the central hubs. Each hub is equipped with an advanced Delivery Barcode Sorter (DBCS). The size of these monster devices varies depending on the installation. But they can easily be several hundred feet in length. Following the introduction of the DBCS machines, the original CSBCS units were decommissioned and stored in a warehouse facility in Topeka, KS. Destined for the scrapheap, their future looked bleak until….

To get a feel for the CSBCS technology, I highly encourage you to watch this video released by the Smithsonian. Their 1994 patent also provides a good overview of its workings. The cameras used by CSBCS machines to scan POSTNET barcodes were known as Wide-Angle Bar Code Readers (WABCR). Before WABCR cameras, the barcode reader had to be lined up directly over the barcode to decode it. This required barcodes to be placed at exactly the same distance from the edges of the envelope, which proved to be surprisingly challenging. WABCR mitigated this issue, but it was soon after replaced by the superior wide field of view (WFOV) cameras from Lockheed Martin:

Deployment of more than 9,000 wide field of view (WFOV) cameras was completed in early 2004. The WFOV cameras replaced the aging and obsolete wide area barcode readers (WABCRs) on all existing DBCS, DIOSS, and carrier sequence barcode sorter (CSBCS) machines. This camera system can read information based indicia (IBI) codes and demonstrated a significant improvement over the WABCR in reading Postal Numeric Encoding Technique (POSTNET) and Postal Alpha Numeric Encoding Technique (PLANET) barcodes.

Unfortunately, there is little to no public information on their internal workings. Furthermore, as I understand it, none of these technologies are in use today. As they say, the moving finger writes; and, having writ, moves on.

Anyways, amidst all these assortments, I found a new hobby — philately, or stamp collecting! The National Postal Museum seems to have a partnership with the Mystic Stamp Company, whereby, upon filling out an online form, you can get two hundred free stamps delivered within a week. And lo and behold, I did just that!

As it turns out, philately is a surprisingly inexpensive hobby. You can buy these $10-$20 packets filled with hundreds of U.S. and international stamps from sites like Etsy and spend countless hours going through them, checking out their history, sorting them, and finally arranging them neatly in a book. All you need is a $4 pack of 1,000 stamp hinges, a $4 magnifying glass, a $5 acid-free sketchbook with thick pages, and a $1.50 pair of tweezers. And that’s really it.

Long gone are the days when stamp collecting used to be an investment. In fact, many stamps have been depreciating in value for quite some time now. This is no longer the Churchill and Roosevelt era. My recommendation? Treat it as a hobby, and you’ll enjoy every second of it. Here are some interesting stamps I got from the Mystic Stamp Company:

Now, one of the things about U.S. stamps is that, to the best of my knowledge, they have never released a stamp series showcasing the U.S.’ technological advancements in computers and computer science. A tad bit surprising, if you ask me, considering the fact that the country has produced stamps featuring Mickey Mouse, Wile E. Coyote, and even Popeye, the spinach man. So I thought to myself, can I create stamps using generative AI? One thing led to another, and I ended up with the crazy idea of mixing artistic styles with such stamps.

For instance, what would you get if you combined the realism of the Renaissance, like Da Vinci’s works, with the Antikythera mechanism? How about Salvador Dalí’s surrealism on a stamp featuring a vacuum tube? Van Gogh’s impressionism with transistors? Matisse’s fauvism with the internet? Picasso’s cubist style plus artificial intelligence? Jackson Pollock’s drip-madness with emails? Edward Hopper's urban realism + hacker culture? And finally, Monet + Silicon Valley?

After trial and error, and some more trial and error, and even more trial and error, here’s my Computing Stamp Series:

I used Dall-E 3 to generate these images. To make them detailed, I started with a skeleton prompt, which was expanded into a more detailed prompt using GPT 4o, which in turn went on to create the images. It was important not to use the word “Picasso” or “Monet” in the prompt, as our young Padawan has a tad bit of phobia when it comes to such words. Wink, wink. To give you an example, here is the exact prompt I used to generate the Picasso stamp:

Create an upright, stamp-sized illustration in a Cubist style, depicting an abstract concept of artificial intelligence (AI) through fragmented and geometric shapes. Use layered panes and interconnected elements to symbolize complexity and networks, incorporating abstract motifs like flowing lines, interconnected nodes, and stylized patterns resembling data flow or neural circuits. Avoid literal depictions of human faces or detailed realism, instead focusing on abstraction and dynamic compositions.

The illustration should feature a muted color palette with occasional bold contrasts, evoking depth and intrigue. The image must fit strictly within the stamp area, surrounded by classic postage stamp perforations along the edges. The area outside the stamp (above, below, and on the sides) must be completely empty, filled with pitch black. There should be no background within the stamp area itself, only the Cubist abstraction of AI.

On the top right corner, engrave "USA" subtly in a bold, vintage serif font that complements the Cubist and old-school aesthetic. Ensure the proportions are balanced, the composition is centered, and the dimensions are precise to fit neatly inside the stamp’s perforated borders. The focus should remain entirely on the artistic and abstract interpretation of AI while adhering to the strict stamp-sized format.

And that’s it, folks! I would have preferred to take a jab at non-fungible tokens, but I’m a bit disinterested in doing so. Safe to say, the generative AI work above is nothing more than a transitionary piece to admire. I have quite a few technical blog posts lined up next. In the meantime, I hope you enjoyed this bottle episode. Until next time! Happy exploring!